By Peter Lawton, First Grade Teacher

This is the second of a two-part “peek” into the first grade and the four ‘R’s of Waldorf education. The first part explored the first three ‘R’s—reading, ‘riting, and ‘rithmetic. This second part addresses the fourth ‘R’—regulation.

The curriculum of the Waldorf first grade—of the first five grades, really—may be summed up as follows:

- Learn basic literacy and numeracy skills (i.e., reading, ‘riting, and ‘rithmetic)

- Learn how to learn (i.e., regulation)

Regulation—The Fourth ‘R’ of Waldorf Education

Regulation (AKA self-regulation) is the ability to understand and manage our behavior and our reactions to feelings. It includes being able to:

- regulate reactions to emotions like frustration or excitement

- calm down after something exciting or upsetting

- focus on a task

- refocus attention on a new task

- control impulses

- learn behaviors that help us get along with other people

Regulation skills develop throughout childhood and enable us to make plans, choose from alternatives, control impulses, and inhibit thoughts. Positive regulation skills are highly correlated not only with academic achievement, but with increased social competence, more intimate interpersonal relationships, and higher self-esteem and self-efficacy throughout life.

The two most prevalent learning challenges facing modern children—ADHD and clinical anxiety—may be understood as imbalances in self-regulatory systems, each representing an imbalance towards one of the two extreme ends of the regulation continuum. ADHD may be understood as too little regulatory control, and clinical anxiety may be understood as the exertion of too much control.

Effortful Control and Negative Affectivity—Two Important Facets of Regulation

Effortful control refers to our ability to voluntarily inhibit a dominant response (e.g., waiting our turn instead of interrupting). And, as you may imagine, high effortful control is associated with more effective regulation.

Negative affectivity refers to our natural human tendency to focus on negative outcomes or possibilities. After all, systems tend to fall apart (entropy); destruction is just so much easier than construction (e.g., it takes months or years to build a house and only moments to burn it down); and we are evolutionarily hardwired to focus on problems (can you say predators?!). An individual who is able to more effectively “bracket” a negative experience, that is to say, an individual who can give a negative experience its proper weight relative to other experiences (e.g., not letting one criticism ruin a day with 99 positive affirmations), is said to have low negative affectivity. And, as you may imagine, low negative affectivity is associated with more effective regulation.

Under-Management, Over-Management, and Flexibility

Regulation concerns the management of our behaviors, including our reactions to feelings. Ineffective management is demonstrated by the tendency to under- or over-manage. Effective management is demonstrated by flexibility.

Individuals who under-manage may exhibit hyperactivity, impulsivity, or aggressiveness.

Individuals who over-manage tend to hold onto or fetishize negative emotions and thought patterns, and they may exhibit shyness, anxiety, perfectionism, and obsessive tendencies.

Effective regulation, on the contrary, is demonstrated by flexibility. Flexibility is the ability to spontaneously choose a response from a wide range of possible actions or reactions. Flexibility is like having a regulation tool kit, as well as the knowledge of how to use all the different tools!

Recommendations for Promoting Effective Regulation at Home and School

We may promote effective self-regulation in children through holistic and developmentally appropriate practices.

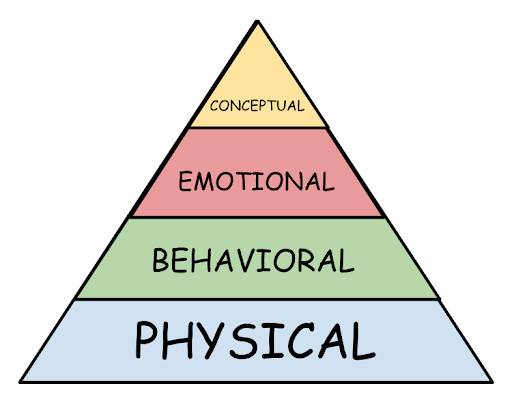

Holistic approaches to promoting regulation address all the aspects of our being, not just our intellects, but our bodies and feelings. In other words, holistic approaches address not only our heads, but our hearts and hands too! Holistic approaches address the following domains: physical, behavioral, emotional, and conceptual.

- Physical recommendations: Ensure proper exercise, diet, sleep, etc. Set the “lay” of the land. “Enclose” a safe but challenging environment in which to play and work. Keep out dangerous or developmentally inappropriate stimuli and keep in appropriate challenges. Limit distractions. Allow freedom of movement within the protected environment.

- Behavioral recommendations: Implicitly show how to behave by example. Tell stories that provide living examples (not exhortations or admonitions) of how to be and act in the world. Speak in images, pictures, and analogies. Consistently enforce some simple, concrete, explicit rules and expectations. Work with the natural rhythms of the day and seasons—let the day and year “breathe” by providing a mix of active and quiet, individual and group, fun and challenging activities. Establish and practice regular habits and routines. Break large tasks into smaller, bite-size pieces.

- Emotional recommendations: Help calm and relax. Acknowledge feelings (e.g., “It’s OK and natural to be afraid.”). Name/label feelings (maybe give recurring negative feelings a name like the “Blue Meanies”). Help distinguish feelings from thoughts (e.g., the feeling of worry is different from the thought pattern or belief that one is incompetent or that something bad is going to happen). Help children face and deal with difficult emotions (e.g., acknowledge fears but help children develop strategies for facing their fears).

- Conceptual recommendations: Help children think “out loud.” Don’t expect them to come up with solutions on their own, but work cooperatively with them to come up with solutions together. Help set short-term goals. Help identify different possible interpretations of negative events (e.g., “Everyone makes mistakes,” “All friends argue sometimes,” and “It’s OK that you’re not the fastest—you’re good at lots of other things.”). Help identify ways situations might be managed differently (e.g., “I could have asked a grown-up for help,” or “I could have walked away.”). Help identify situations to seek out or avoid in the future.

Developmentally appropriate approaches to promoting regulation understand what children of different ages can and cannot do:

- Young children ages 2-6 are primarily sensory-motor learners—they learn through doing!

- Elementary-age children ages 7-12 are sensory-motor and imagistic learners. In addition to learning by doing, elementary-age children learn through symbolic representations such as stories, play, art, analogies, miming, and playacting—through feeling!

- Adolescents ages 13 and above learn by doing, feeling, and increasingly, as they approach adulthood, through mentally manipulating concepts or ideas—through thinking!

As we may gather from the paragraphs above, first-graders are concrete thinkers. They understand through experiences and living images, NOT through concepts; they understand through examples, NOT definitions; they understand through concrete representations of ideas-in-action, NOT abstract explanations!

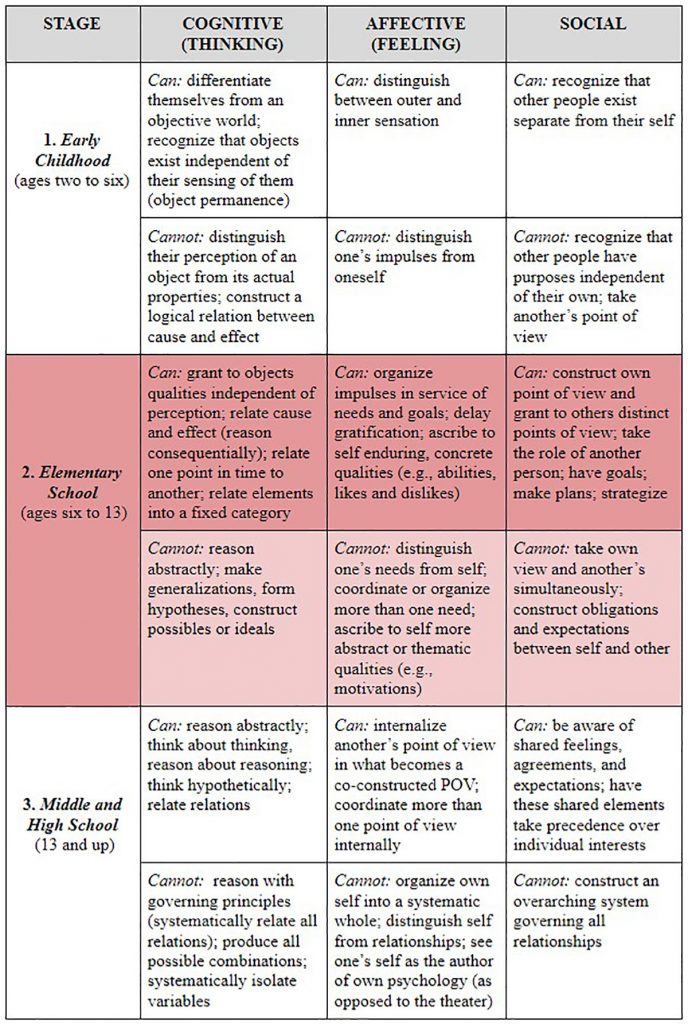

As concrete thinkers, and as we may see in the following chart, first-graders and other elementary-age children CAN understand cause and effect; they CAN set and work towards some simple goals, and they can delay gratification for increasingly longer periods of time.

But there’s a fascinating and important developmental distinction to be made here, and it’s demonstrated more by the ‘CANNOTS’ than the ‘CANS.’ While a concrete-thinking grade-schooler CAN take another’s point of view—say, a frustrated Mommy’s, teacher’s, or friend’s—they CANNOT construct a general principle that relates or encompasses their point of view with the other’s. They CAN understand, for instance, that they’re sad and Mommy’s frustrated. What they CANNOT do is make sense of a world that contains sadness and frustration at the same time! They need our help to do that! (See some of the holistic recommendations listed above.)

Similarly, while concrete-thinking grade-schoolers CAN articulate what they want in the moment—for instance, they can say, “I don’t want to do math!”—they CANNOT articulate the underlying emotions and motivations that contribute to their math aversion. Identifying underlying emotions and motivations requires the ability to generalize and abstract. In other words, while first-graders may find it easy to say what they want, they need our help to understand what they actually need. (Again, see some of the holistic recommendations listed above.)

Children need our loving, adult help to learn how to effectively self-regulate!

Oh, and I forgot to mention the fifth ‘R’ of Waldorf education—recess!

Read More:

- A Peek Into First Grade: Part I by Peter Lawton

- “The Evolution of Meaning: Robert Kegan’s Psychology and the Three Stages of Development in Childhood” by Peter Lawton, Research Bulletin 25 (2020)