By Jessica Crawford, 8th Grade Teacher

The Waldorf approach to history is founded on the idea that human consciousness has evolved over time—and is still evolving. An important point to make right off the bat, and one that has dawned on me only recently, is that evolution does mean change, but does not necessarily mean change for the better on a linear trajectory, or improvement over time. At the same time, we certainly hope that humanity is becoming more aware and awake to our inner selves and our individual and community impact upon others and the world.

As we consider which biographies to tell to provide a human-centered, individual window into the movements and complex facets of history, we Waldorf teachers keep central in our minds the developmental stage of the children in front of us. What are the primary soul gestures from human history that especially speak to and harmonize with the students’ current phase? In order to fully answer that question, it is vital to look at the students themselves and their cultural and ethnic make-up, and at the same time to look out at the world, at current events. That is an ever-changing picture, and keeps me on my toes, yet I also strive to provide the stability and assurance of shared and deep human themes and motifs that we see arising out of particular epochs and communities throughout history.

“Positive social and cultural change—and the development of consciousness—need to go hand in hand, if we are to see a just society, one with protection of and equal rights for all people, emerge out of any epoch.”

In 8th grade, American History is usually taught over two blocks, beginning before the arrival of Europeans to the east coast of our country, with a cultural study of some of the 15 million diverse Indigenous peoples who had already been living here for thousands of years. First, we considered land—where human activity occurs—as the primary element of history: land walked upon by those in the present as well as their ancestors; land fought over and upon which blood and tears have been shed; and land tilled and tended, bringing forth a means of sustenance for life. It seems that land is life. In the histories of nations and groups of people, water often follows directly behind land as another vital and directive element of the earth we share; access to and use of water becomes equal to health, wealth, and power. Conflicts over natural resources such as land and water are not just history, clearly, but persist today.

When we considered the arrival of the first Europeans, subsequent waves of immigrants, and the enslaved people who were brought here against their will and under the most unimaginably awful conditions, we also looked at the conditions out of which this movement of people on the earth occurred, including economic, religious, and cultural realities. Our first block ended with the end of the Civil War, after a good hard look at the American Revolution and its impact on other parts of the world, the origins of racism, the establishment of and dependence on the enslavement of Africans in the “New World” starting in 1619 with the arrival of the first 20 African slaves, Lincoln’s assassination, and the start of the Reconstruction Era.

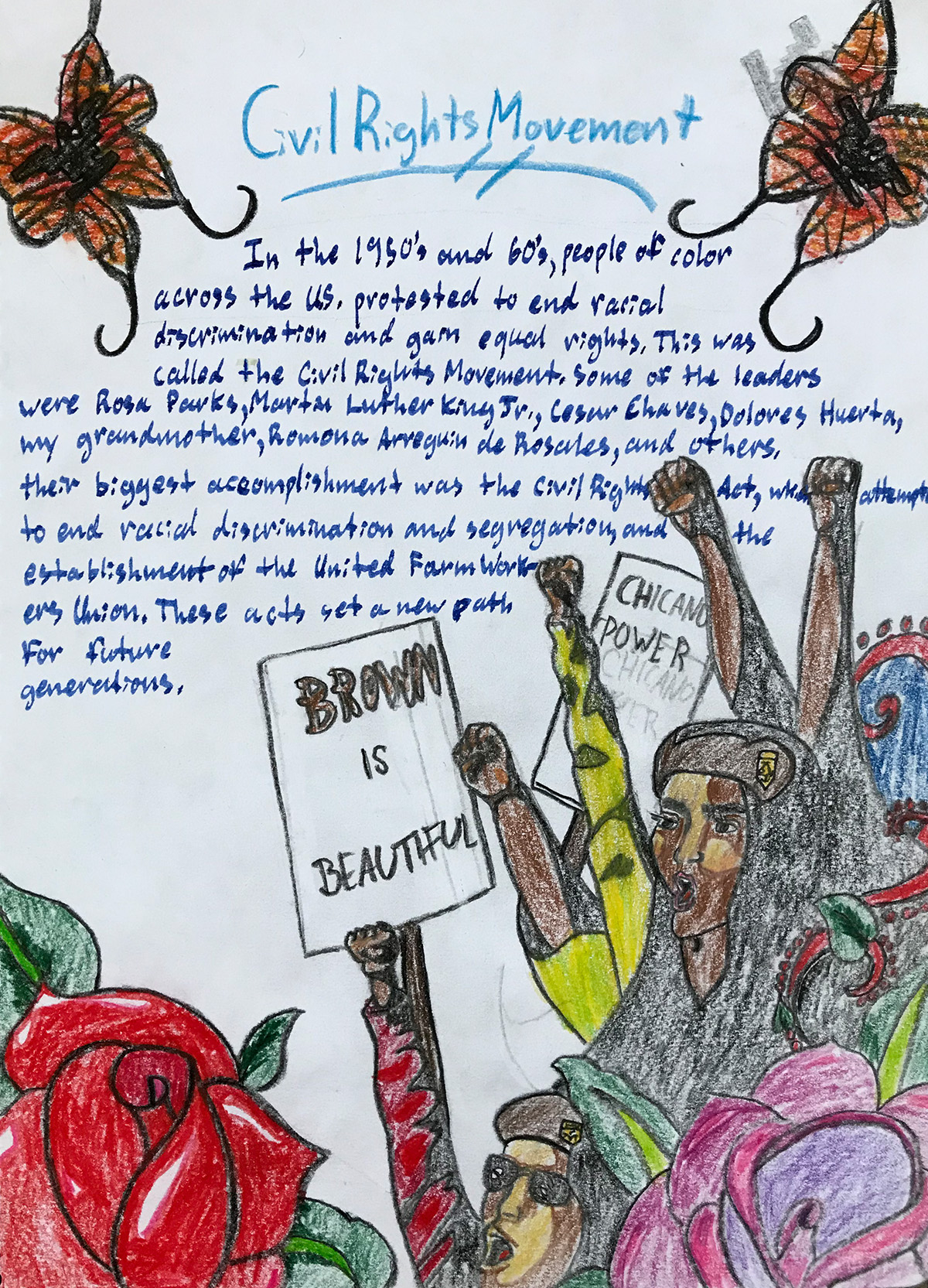

The second block, in January of this year, moved through the successes and failures of the Reconstruction Era in terms of the rights of all people to all of the benefits of citizenship under the protection of our Constitution, the Industrial Revolution and its impact on individuals and the society as a whole, the expansion of European land ownership westward and its effect on Indigenous and African-American peoples, and the Civil Rights Movement’s origins, methods, and key participants.

Through all of our American history studies, we used Howard Zinn’s A Young People’s History of the United States as a reader, and read excerpts from Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’ An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States and Jason Reynold’s Stamped—a book for young people about racism and its origins and pervasive presence in our society. These resources provided the students with perspectives that somewhat overlap, yet tell the story of American history through particular and essential lenses.

All through our studies, and particularly when we studied the Civil Rights’ Movement, we often bumped up against the violence of taking others’ land and livelihood, and of enslavement and deprivation of rights. To learn a fuller history, we also studied the individual biographies of people of courage, bravery, and determination. Some of these voices are: Chief Powhatan; Frederick Douglass; Sally Hemings; Abigail Adams; Phillis Wheatley; African-American cowboys, such as Billy Pickett; Homer Plessy, who boarded a train in 1892 and purposefully sat where he was forbidden; Rosa Parks; Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; the Freedom Riders; and the Little Rock 9, among many others.

According to the historian Howard Zinn, America’s true greatness is shaped by our dissident voices, not our military generals. Positive social and cultural change—and the development of consciousness—need to go hand in hand, if we are to see a just society, one with protection of and equal rights for all people, emerge out of any epoch. As the mural at Lyndale and Lake proclaims, with an image of hands busy working with cans of spray paint, Black Lives Matter – All Year Long.